Module 4: AI robustness- Benchmarking Adversarial Robustness for Image Classification

Deep neural networks subject to adversarial examples has become one of the most significant research issues in deep learning. One of the most difficult aspects of benchmarking robustness is that its assessment is frequently prone to inaccuracy, resulting in robustness overestimation. The research on adversarial robustness is faced with the absolutes between attacks and defenses. Defensive methods proposed to prevent existing attacks became outdated as new attacks emerge. Therefore it’s hard to truly understand the effects of these methods. In this paper, we investigate various thorough, rigorous, and coherent benchmarks for evaluating adversarial robustness on image classification tasks.

- Introduction

- Datasets And Adversarial Training Properties

- Evaluation of existing methods

- Concluding Remarks

- References

Introduction

Deep neural networks have demonstrated outstanding performance in a variety of applications. However, they are still vulnerable to adversarial examples; that is, intentionally constructed perturbations that are imperceptible to humans might easily cause DNNs to make incorrect predictions. This presents a threat to both digital and physical deep learning applications. Furthermore, previous research has shown that DNNs are susceptible to natural disturbances. These events show that deep learning algorithms are not intrinsically safe and reliable. Since DNNs have been integrated into a variety of safety-critical scenarios (e.g., autonomous driving, facial recognition), strengthening model robustness and further developing robust deep learning systems is becoming increasingly important. Benchmarking the robustness of deep learning models is an important step toward a better understanding and improvement of model robustness.

Previously, several investigations have shown that convolutional networks are vulnerable to simple corruption. It is well known human vision outperforms convolutional networks in terms of robustness, even after networks are fine-tuned through adversarial training to handle distortions. Despite these efforts, research has shown that fine-tuning for one form of distortions(blur) is insufficient to generalize to others[2]. Furthermore, fine-tuning on multiple blurs only slightly reduces performance but is a resource intensive and can potentially result in underfitting[2]. These shortcomings and the desire to build truly robust models led researchers to study the effects of adversarial learning at scale[5] and introduce datasets that test the robustness of the model[1][3]. Finally, once trained, we need a benchmark of models which aims at standardized adversarial robustness evaluation. Experiments on the cross-evaluation of the attacks and defenses are performed on these models to evaluate the robustness[5][6].

In the following sections, typical methods from each approach are summarized, analyzed, and compared.

Datasets And Adversarial Training Properties

MNIST-C: A Robustness Benchmark for Computer Vision

Brief Summary

In this paper, the authors introduce a new dataset called MNIST-C for benchmarking robustness of computer vision models on out-of-distribution samples. It extends some of the work done in IMAGETNET-C but specifically for the MNIST dataset. They showcase that this new MNIST-C dataset causes an increase in error rate for common neural networks, showcasing that there is still much more to be done on improving the robustness of deep neural networks.

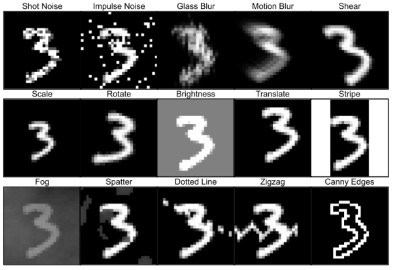

Initially, the authors start with 31 possible image corruptions based on prior literature on robustness and image processing. Out of these, they were able to benchmark 15 different corruptions that tended to have the most adverse effect on augmented data trained CNN model performance. These 15 include - shot noise, impulse noise, glass blur, motion blur, shear, translate, scale, rotate, brightness stripe, fog, splatter, zigzag, dotted line and Canny edges. Each of the corruptions itself is further parameterized by a severity metric such that a model’s performance is affected by not the semantics of the content. Each of the different perturbations can be seen in the figure below.

Furthermore, the authors took 4 additional metrics to select candidates for the dataset.

- Non-triviality - Corruption should degrade the testing accuracy of different models.

- Semantic Invariance - Humans should be able to understand the transformation.

- Realism - Corruptions that are possible in the real world.

- Breadth - Using minimal number of corruptions to make sure the dataset isn’t too large.

The dataset was then evaluated against the following models:

- CNN(Conv1) trained on clean MNIST

- CNN (Conv2) trained against PGD adversarial noise

- CNN (Conv3) trained against PGD/GAN adversaries

- Capsule network

- Generative Model, ABS

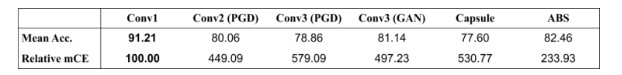

This paper then uses the same metric mCR[1] to analyze the error rates of the models on the MNIST-C dataset. The results are given in the figure below.

This Figure shows the mCE of the different convolutional models tested in this paper.

Analysis

Table one and the relative mean corruption rate results showcase a surprising result. Note that the mCR is a metric that measures performance degradation when encountering corruption. This result indicates that the most effective model for dealing with MNIST-C is a simple CNN trained on clean MNIST: it has the smallest mCE when compared to the other models. One possible explanation for this is due to the fact that the MNIST-C data set is built such that the images are corrupted beyond a threshold that makes the corruption easily recognizable for humans but will degrade neural network performance. Such datasets are significantly more likely in the real world implying that hedging for adversarial robustness does not necessarily prepare a model for real-world datasets. Adversarial models are effectively searching for cases that are fine-tuned to make models fail without considering the realism of the dataset. Hence, although they are robust against nefarious attacks that aim to perturbate the data without impacting semantics, they miss rather obvious corruption that is easy for humans to interpret. As suggested by the authors, this notion of robustness is more practical for machine learning in noncritical applications.

Finally, the authors of the paper disregarded horizontal and vertical flips. These transformations are very likely to occur in the real world. Furthermore, they are far more likely to degrade performance across the board but are out-of-distribution transformations that are both semantically meaningful and easy to identify with humans. MNIST-C could benefit from including these transformations to test for robustness in this regard.

Benchmarking Neural Network Robustness to Common Corruptions and Perturbations

Brief Summary

This paper establishes rigorous benchmarks for image classifier robustness[1]. They introduced 2 new datasets, the IMAGETNET-C dataset for input corruption robustness and the IMAGENET-P dataset for input perturbation robustness. This benchmark evaluates performance on common corruptions and perturbations instead of worst-case adversarial perturbations. Corruption robustness measures the classifier’s average-case performance on corruption. Perturbation robustness is defined as the average-case performance on tiny, generic, classifier-independent perturbations; i.e. assessing perturbation resilience and tracking the classifier’s prediction stability, dependability, or consistency in the face of modest input changes.

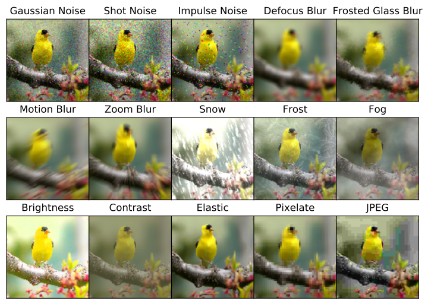

IMAGENET-C ImageNet validation photos were subjected to 15 different types of corruption. There are five levels of severity for each sort of corruption, totaling 75 unique corruptions. Noise, blur, weather, and digital are the four basic forms of corruption. Because the corruptions are diverse and numerous, research that improves performance on this benchmark should show broad robustness advantages.

IMAGENET-P Noise, blur, weather, and digital aberrations are all present in IMAGENET-P, just as they are in IMAGENET-C. IMAGENET-P differs from IMAGENET-C in that each ImageNet validation image generates perturbation sequences. Models with poor perturbation robustness give irregular predictions, eroding user confidence.

To evaluate the performance of these models on these datasets, two evaluation metrics were introduced. The first one is mCE which stands for mean corruption error and the second one is relative mCE. The definition of these two metrics is given below. Both of them are measured measured against AlexNet as a baseline. Check paper for description about the variables in the equation[1]. In short, they are designed to measure the effectiveness of the model to deal with the corrupted datasets introduced above.

\[CE_c^f = \frac{\sum_{s} E_{s,c}^f}{\sum_{s} E_{s,c}^{AlexNet}}\] \[CE_c^f = \frac{\sum{s} E_{s,c}^f - E_{clean}^f}{\sum_{s} E_{s,c}^{AlexNet} - E_{clean}^{AlexNet}}\]Analysis

The main results of the paper can be seen in the figure above. The findings in the paper indicate that the mean Corruption Error improves as architectures have improved. By this metric, architectures have been better at generalizing to corrupted distributions over time. CEs are pretty similar in models with similar clean error rates. Interestingly many models following Alexnet have lower relative mCEs. As a result, the corruption robustness of AlexNet to ResNet has barely changed when measured by the relative mCE.

Intriguing Properties of Adversarial Training at Scale

Brief Summary

The goal of this paper is to investigate some properties of adversarial training on a large scale like on ImageNet. Certain architectures and ideas have become commonplace in deep learning like batch normalization and deeper networks with the aim to improve generalization. The study finds two properties related to BN and deep networks in the context of robustness. First, batch normalization may not be effective in improving robustness at the ImageNet scale. Second, deep networks are still “shallow” in the sense that adversarial learning incurs strong demand to achieve higher robustness but it may be worth it.

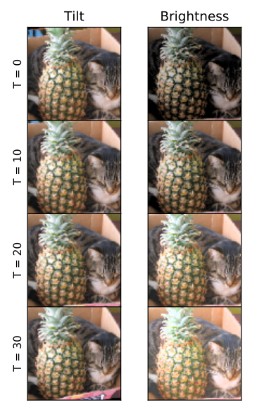

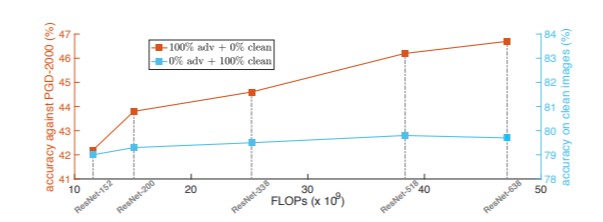

To explore these findings, the authors use a ResNet-152 model and projected gradient descent as the adversarial attacker. They employ different adversarial training strategies (check paper for hyperparameters). In short, the findings reveal that training only on adversarial images without including clean images is more robust than combining the two. The results are evident in the figures below.

This figure shows the attackers effectiveness after training for 2000 iterations on models trained with different strategies with different datasets.

This figure shows the relationship between the ratio of clean images and model robustness.

Both of the figures above indicate that the accuracy against PGD improves as the number of clean images is reduced. In the first image, the PGD method’s effectiveness reduces asymptotically when the model is trained without clean images while in other cases there is no observed performance level off.

Next, they try to identify a reason for this failure and a possible approach to fixing it. The authors call the culprit the two-domain hypothesis: adversarial images and clean images are drawn from different domains and normalization statistics across both domains are challenging to perform simultaneously. To test this idea, they train a model by employing a pair of BNs’ to work with minibatchs of data from the different domains (adversarial vs clean image). The results shown in the figure below indicate that separating out BN’s like this does in fact reduce the effect of PGD on the trained.

This figure shows that employing different sets of BN.

One can see from the figure above that the performance, in this case, appears to be more stable than before. Where previously, PGD affected the model significantly, the dramatic drop in performance is not observed in this case.

Finally, the authors test the impact of network depth in improving robustness in adversarial training. Typically, ultra deep networks employing the usual training strategies have diminishing returns on performance. Interestingly, this appears not to be the case with adversarial training on only adversarial images. This result is evident from the figure below.

This figure shows how the depth of a network’s impact on performance is

Furthermore, one additional observation that the authors present is that convolution filters trained to extract features on adversarial images are effective for both clean and adversarial images but the inverse is not true. This indicates that employing adversarial training may incur computational costs during training but because the filters can handle both adversarial and regular inputs they may be crucial for critical systems that would benefit from the added protection.

Analysis

When considering the normalization statistics and the two-domain hypothesis, the results in regards to the impact of batch normalization are not surprising but are very informative. Batch normalization has become customary in deep learning applications and these results showcase its limitations when performing adversarial training. There are several avenues to take these findings further. It would be interesting to see if they also hold up for datasets that are much smaller than ImageNet and if performance levels off for ultra deep networks. Oftentimes, datasets are not as large as ImageNet and the extensive use of BN could be detrimental to building robust networks trained using adversarial strategies.

Finally, one of the proposed methods to improve robustness is to simply build more deep networks. Although this does yield better results, it’s important to consider if robustness though depth is “worth it”. Ultra deep networks consume an enormous amount of energy and computational resources to train and maintain. This presents obvious ethical considerations like access to and consumption of these resources.

Comparison

The first two papers discussed above are similar in the sense that they both introduce new datasets, MNIST-C, IMAGENET-C, and IMAGENET-P. All of these datasets were designed by corrupting the source image with the intent of designing effective testing set for the robustness of adversarial trained neural networks. They all utilize the mean corruption error as a metric for determining the robustness of adversarially trained models against these three datasets. The effectiveness of this metric is evident from the mCE for various different models seen in figure above. Finally, these datasets are designed to test practical robustness rather than robustness against adversarial attackers like PGD. PGD is designed to find adversarial images that are fine tuned to fool models but the image corruption itself is subtle enough that it is not noticeable. The final paper discusses improving this robustness in some regard.

The last paper is concerned purely with adversarial training, its properties, and how to exploit knowledge of these properties to improve robustness. It is more focused on architectural choices and training paradigm to improve the overall robustness of the model. The results indicate that robustness can be improved by employing separate batch normalization or training models purely on adversarial images with zero “clean” images. The objective then is for the model to discover the corruptions during adversarial training and learn steps to combat them. It would be interesting to see how a modified model would fare against the MNIST-C, IMAGENET-C and IMAGENET-P datasets introduced in the first two papers. One could see how well they hold up against ultra deep networks as results from the final paper indicate that network depth can improve robustness. Given that these datasets were designed with practical robustness in mind, it may present a significant challenge in both cases: the types of corruption seen in them may be too abstract for purely adversarial training to handle.

Evaluation of existing methods

Benchmarking Adversarial Robustness on Image Classification

Brief Summary

The goal of this work is to develop a benchmark to comprehensively evaluate the adversarial robustness of the existing methods and serve as a useful standard for future work.

To build a robustness benchmark they first define the threat models which state how an attack is performed and in which situation a defense is robust. There are three aspects of a stress model described in this paper. The first one is the adversary scope, which can be categorized into untargeted attacks and targeted attacks. The second one is the adversary’s capabilities in this work. They only consider l2 and l-infinity norms. The third one is the adversary’s knowledge. White box attacks, transfer-based attacks, score-based black-box attacks, and decision-based attacks are taken into account. A lot of typical attack methods for the robustness evaluations are used. The defenses are roughly classified into five categories which include robust training, input transformation, randomization, model ensemble, and certified defenses. There are 16 typical certified defenses on CIFAR-10 and ImageNet. These models cover all different categories and include the state of the art in each category.

For evaluation, two robustness curves are proposed to fully show the performance of attacks and defenses. The first one is the attack success rate versus perturbation budget curves. This gives a global understanding of the robustness of the class sphere and the effectiveness of the attack. The second one is the accuracy of the attack success rate versus the attack strength curve. This curve can show the efficiency of the attack.

Analysis

Experiments on the cross-evaluation of the attacks and defenses are performed for example under the l-infinity and targeted white-box attacks. The accuracy curves of the eight defenses on CFAIR-10 are calculated. The most robust models are found to be the ones that are adversarially trained. Another finding is that the relative robustness between two models against an attack could be different under different perturbation budgets or attack iterations. This finding implies that the cooperation between the defense models at a chosen perturbation budget or attack iteration, which is common in previous works, cannot fully demonstrate the performance of a model. But the robustness curves adopted in this paper can better show the global behavior of these methods. In the end, they created a platform where people can test the robustness of their model.

RobustBench: a standardized adversarial robustness benchmark

Brief Summary

RobustBench, which is introduced in this study, is a benchmark for adversarial robustness. The benchmark focuses solely on the challenge of adversarial robustness in image classification models under threat models of l-infinity and l2 perturbations, as represented by the attacks implemented in the auto-attack package, allowing for a specific set of defenses in the benchmarked robust models. The benchmark gives an upper bound on robustness using AutoAttack, which eliminates the requirement for third parties to do time-consuming adaptive evaluations per defense. AutoAttack provides appropriate bounds for defenses that adhere to a set of rules. RobustBench presently does not support defenses that break these rules. RobustBench allows third parties to submit findings from adaptive attacks if AutoAttack does not give a tight bound on a given defense. In addition, it also analyzes the impact of robustness on the performance of distribution shifts, calibration, out-of-distribution detection, etc.

A model zoo for adversarially robust models is also included in the work, allowing researchers a consistent interface to over 80 robust models proposed in the literature. Finally, the paper examines various robust models that are made possible by the model zoo’s unified API.

Anaysis

There are over 3000 papers have been published on the subject of adversarial examples, with a major fraction of these articles suggesting new strategies for training robust models and defending against adversarial examples. The community requires a systematic way to catalog and evaluate these defenses. RobustBench is the best attempt to date at solving this problem, overcoming the limits of previous work such as robust-ml.org.

RobustBench provides a number of useful insights. One is that many viable defenses meet the following criteria:

- Differentiable

- Deterministic

- Devoid of optimization loops.

The other is that AutoAttack, a parameter-free assault that runs versions of various well-known white-box and black-box attacks, frequently provides reasonable upper bounds for defenses that satisfy that set of constraints.

Based on AutoAttack, a benchmark/leaderboard can be used to compare defenses even if they haven’t been thoroughly analyzed by third-party researchers looking to perform an adaptive attack, making the benchmark considerably more helpful overall. It’s simple and useful to add a new defense to the benchmark. RobustBench understands that AutoAttack isn’t flawless, thus it also accepts adaptive attacks against certain defenses.

Comparison

Both papers create a platform which can evaluate the robustness of a model. Both focus on the challenge of adversarial robustness in image classification models under threat models of l-infinity and l2 perturbations. Each of the papers introduce separate benchmarks, RealSafe[5] and RobustBnech[6]. RobustBench is much better than RealSafe, as it contains more number of models and accounts for both attack and defense. RealSafe has its own metric curve to demonstrate the robustness of the model. On the other hand, RobustBench also analyzes the robustness under distribution shifts, calibration, out-of-distribution detection, fairness, privacy leakage, smoothness, and transferability. Additionally it uses AutoAttack[6], which runs versions of various well-known white-box and black-box attacks. Finally, they introduce a model Zoo, which perform evaluations on a large set of more than 80 models. Unlike Robustbench, the other study only provides a list/implementation of models for evaluation[5]. The finally contribution from RobustBench is most importantly: a leaderboard ranking to track the progress and the current state of the art in adversarial robustness.

Concluding Remarks

In this paper, we look at robustness in the context of adversarial training. Each of the studies we looked at focuses on different aspect of deep learning: datasets, architecture, and evaluation. Several studies introduced datasets designed to measure a model’s robustness in any context but particular for models employing advesarial learning[1][4]. These datasets are supported by a new metric for measuring robustness called corruption error[1]. This metric is designed to provides insight on current limitations and the performance improvement of models developed post AlexNet[1]. Additionally, we explore properties of adversarial training and understand how to improve network architecture to squeeze additional performance from models[5]. Finally, we look at two different studies that propose methods for evaluating and benchmarking current and future models[6][7]. Together, these studies indicate that there is still more to explore in this space.

References

[1] Hendrycks, D., & Dietterich, T. : Benchmarking neural network robustness to common corruptions and perturbations. arXiv preprint arXiv:1903.12261 (2019).

[2] Dodge, S., & Karam, L. : A study and comparison of human and deep learning recognition performance under visual distortions. In 2017 26th international conference on computer communication and networks (ICCCN) (pp. 1-7). IEEE. (2017).

[3] Norman Mu, Justin Gilmer: “MNIST-C: A Robustness Benchmark for Computer Vision”. http://arxiv.org/abs/1906.02337 arXiv:1906.02337 (2019).

[4] Cihang Xie, Alan Yuille: “Intriguing properties of adversarial training at scale”. http://arxiv.org/abs/1906.03787 arXiv:1906.03787 (2019)

[5] Dong, Y., Fu, Q. A., Yang, X., Pang, T., Su, H., Xiao, Z., & Zhu, J. Benchmarking adversarial robustness on image classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (pp. 321-331). (2020).

[6] Croce, F., Andriushchenko, M., Sehwag, V., Debenedetti, E., Flammarion, N., Chiang, M., … & Hein, M. Robustbench: a standardized adversarial robustness benchmark. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.09670 (2020).

[7] Yang, Xiao, et al. “RobFR: Benchmarking Adversarial Robustness on Face Recognition.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2007.04118 (2020).

[8] Lorenz, Peter, et al. “Is RobustBench/AutoAttack a suitable Benchmark for Adversarial Robustness?.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2112.01601 (2021).

[9] Tang, Shiyu, et al. “Robustart: Benchmarking robustness on architecture design and training techniques.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2109.05211 (2021).

[10] Sun, Jiachen, et al. “Certified Adversarial Defenses Meet Out-of-Distribution Corruptions: Benchmarking Robustness and Simple Baselines.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2112.00659 (2021).