Module 7 - A Survey on Intervention-based Learning

Intervention-based learning is a modern and rapidly progressing field based on utilizing human interventions in the learning process to train an agent online. Traditionally, imitation learning and DAgger were used to instill human expert knowledge to the learner, but such methods require the human expert to manually label tediously large amounts of data. With this in mind, intervention-based learning has arisen to tackle the need for large amounts of expert queries by learning from periods of uninterrupted human expert control. This paper discusses three key intervention-based learning methods, HG-DAgger, Expert Intervention Learning (EIL), and Human-AI Co-pilot Optimization (HACO). We provide an in-depth explanation of how intervention-based learning improves upon imitation learning and DAgger. In addition to this, we discuss how EIL and HACO, the current state-of-the-art, improve upon HG-DAgger and outperform all other methods discussed while requiring significantly less human annotated data.

- Introduction

- Previous Work

- Intervention-based Learning

- Key Differences Summary

- Conclusion

- References

Introduction

This paper will discuss recent developments in the field of intervention-based learning. We motivate this paper by first reviewing the predecessors of intervention-based learning – imitation learning and DAgger, which use human expert knowledge to train a learning agent. These algorithms have the learner in control, relying on a human expert to annotate a large quantity of states and actions observed by the expert. These annotations are used by the learner to train a policy that performs well under the training data distribution.

We discuss the shortcomings of these algorithms and establish the need for a new paradigm of learning from human expert knowledge. This leads to an exploration of intervention-based learning algorithms which put the human expert in control. These human-in-the-loop learning techniques have a human expert supervise a learning agent during the training process. The human expert can decide when and how to intervene in the behavior exhibited by the learning agent, demonstrating to the agent the correct action. The following intervention-based learning techniques are analyzed in detail in their own sections: HG-DAgger, Expert Intervention Learning (EIL) and Human-AI Co-pilot Optimization (HACO).

Previous Work

Imitation Learning

The purpose of imitation learning is to take advantage of the knowledge and skills of a human expert to train an agent. Human expert demonstrations are provided to the agent to learn an optimal policy that performs the task to a similar degree of proficiency as the human expert. This is contrasted with traditional reinforcement learning, where human knowledge is not used in training, instead a reward function is designed, and the RL agent learns an optimal policy that maximizes reward based only on its own experiences within the environment.

While reinforcement learning can arrive at a similar policy to imitation learning, it can potentially take exponentially longer to do so because of the exploration needed to learn the same policy. Human expert demonstrations reduce the need for exploration and guide the policy to improve much faster, thus motivating the use of expert demonstrations.

There are 2 general categories of methods to achieve imitation learning - Behavior Cloning and Inverse Reinforcement Learning.

Behavior Cloning

Behavior Cloning (BC) is an attempt at getting the agent to directly replicate expert behavior. Given a dataset of human expert demonstrations, the dataset consists of expert states and actions \((s^*, a^*)\). This dataset is used to learn a direct mapping from states to actions without constructing a reward function. This can be framed as a supervised learning scenario where a policy is learned by minimizing some loss function.

BC methods have primarily focused on model-free methods, meaning that they do not explicitly learn or use a forward model of the system. Model-free BC methods are well suited for applications such as trajectory planning of robotic systems.

Inverse Reinforcement Learning

Inverse Reinforcement Learning (IRL) is an attempt at recovering a reward function from the human expert demonstrations, assuming the demonstrations are optimal for the reward function. Subsequently, the reward function and traditional RL is used to obtain a policy that maximizes the expected accumulated reward. IRL is beneficial when the reward function is the best way to describe the optimal behavior.

IRL methods have primarily focused on model-based methods because knowledge about the model is used to evaluate and update the reward function and optimal policy.

Challenges of imitation learning

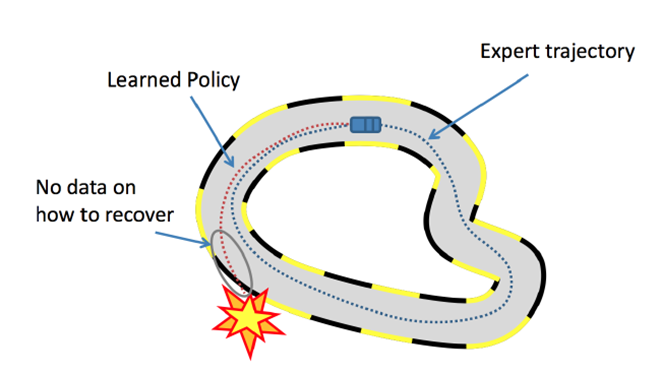

The agent is trained to mimic human expert demonstrations, but this training data does not generalize well. The key problem is that the training data distribution and the testing data distribution are different, causing the agent to end up in states it has never visited before. If an agent makes a mistake, it finds itself in conditions that are completely distinct from what it observed during training, leading to unpredictable behavior. This effect is known as covariate shift.

Figure 1. Failure scenario of behavior cloning.

Another challenge faced by imitation learning is when the human expert demonstrations are insufficient and it is not possible for humans to provide the comprehensive annotations needed to train an agent.

The following sections about DAgger and intervention-based learning methods will attempt to address these challenges.

DAgger

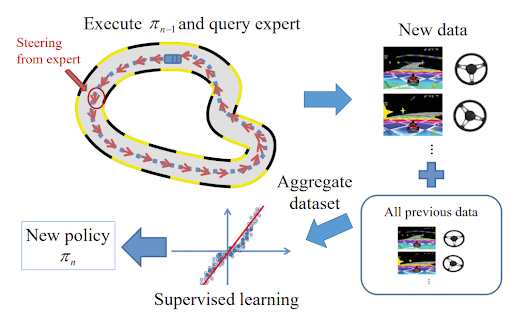

The policy learned using imitation learning methods perform better when close to the distribution of states present in the training dataset. However, errors in such a policy might add up eventually to drive the agent to states which are far apart from what has been seen during training and are hard to recover from. DAgger (Dataset Aggregation) [2] overcomes this problem by collecting data at each iteration under the current policy by querying the expert to label every learner-visited state. In other words, we obtain a dataset of learner state and expert actions pairs \((s, a^*)\). After every iteration, the policy is updated by training on the total aggregate of all collected data.

Essentially, DAgger has made the learning process online and overcome the distribution shift problem as shown below in Figure 2, but require expert annotations for all the new trajectories explored.

Figure 2. DAgger and how it handles the failure scenario of behavior cloning.

Intervention-based Learning

As shown in the previous section, both imitation learning and DAgger style approaches are quite expensive in terms of annotation cost as they require a human expert to label every state and/or action. This annotation cost is not only burdensome on the human expert, but may also become infeasible for complex tasks. To address these issues, intervention-based learning has started to become a popular research direction in the human-in-the-loop learning community. As the name suggests, these algorithms let the learner maintain control during the training process and allows the human expert to intervene and takeover control whenever deemed necessary (e.g. when a self-driving car starts to veer off the road).

As we will show in the upcoming sections, intervention-based learning has several key benefits over imitation learning and DAgger. First, a significant reduction in annotation cost is achieved as the vast majority of state-action pairs are provided by the learner. With the reduction in labeled data, the key to these approaches is to maintain learning convergence.

Second, intervention-based learning approaches allow for much more intuitive (and arguably more correct) annotating by the human expert as they can now control the induced state distribution. Before, DAgger forced a human expert to provide the proper action for the learner-induced state distribution. This asychrony between state and control is difficult for humans to deal with for extended periods of time and can result in degradation in the quality of the annotations.

We go over three key approaches in the intervention-based learning literature that attempt to solve this problem. First, we will go over an intervention-based approach to DAgger called Human-Gated DAgger (HG-DAgger) [3] and discuss the algorithm’s modifications, improvements, and drawbacks. Next, we will go over two state-of-the-art approaches: (1) Expert Intervention Learning (EIL) [4] and (2) Human-AI Co-pilot Optimization (HACO) [5]. For both methods, we will showcase the methodology as well as conduct a detailed comparison between their performances.

HG-DAgger

One of the pioneering works in intervention-based learning, HG-DAgger, applies a simple modification to the original DAgger algorithm and is therefore quite intuitive to understand. In contrast to DAgger, HG-DAgger allows for the human expert to intervene and obtain stretches of uninterrupted control. Whereas DAgger requires the expert to label every learner-visited state \(s\) with an action \(a^*\) and trains over this entire set, HG-DAgger has the learner fully in control until the human expert intervenes. During intervention, only these expert state-action labels \((s^*, a^*)\) are recorded and added to a training data set \(\mathcal D\).

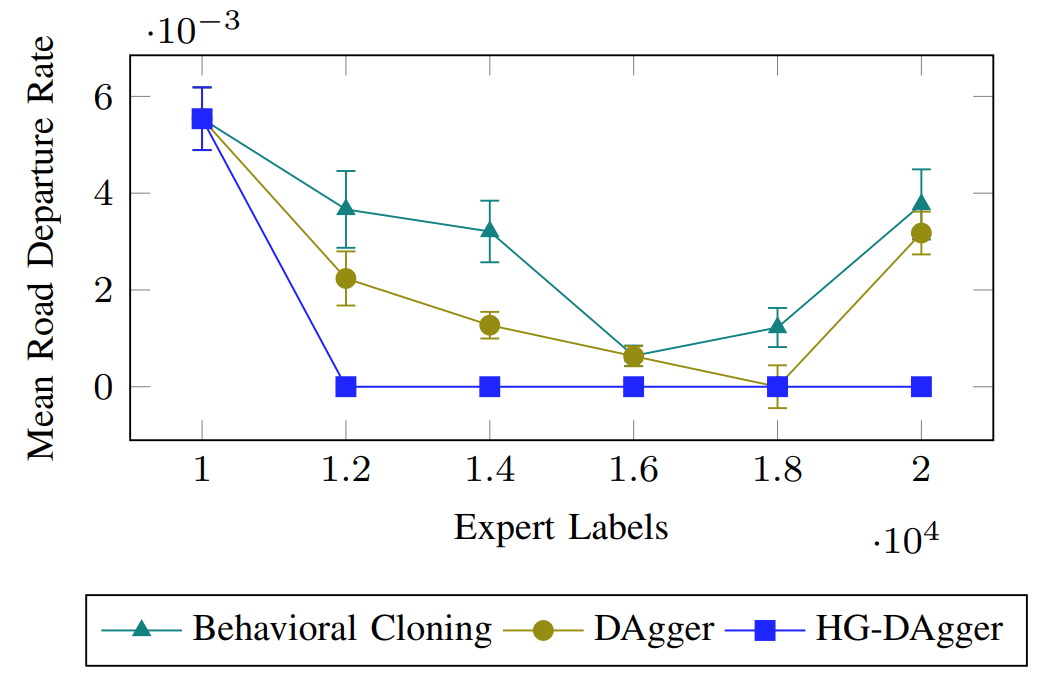

Although HG-DAgger obtains significantly less human annotations than DAgger, HG-DAgger collects data from the human expert only while they have uninterrupted control. Therefore, such state-action pairs can be expected to be of high quality. This learning efficiency can be seen below in Figure 3 where HG-DAgger outperforms both behavioral cloning and DAgger with significantly less expert labels.

Figure 3. Results for a self-driving car scenario experiment plotting mean road departure rate with respect to expert labels. Notice that HG-DAgger achieves and maintains a zero mean road departure rate with significantly less expert labels. [3]

Despite this, HG-DAgger has several shortcomings. For example, although HG-DAgger may perfectly mimic expert recovery, it provides no explicit incentive for the learner to avoid scenarios requiring human intervention in the first place. We see how this drawback is addressed by the next two methods we cover.

Expert Intervention Learning (EIL)

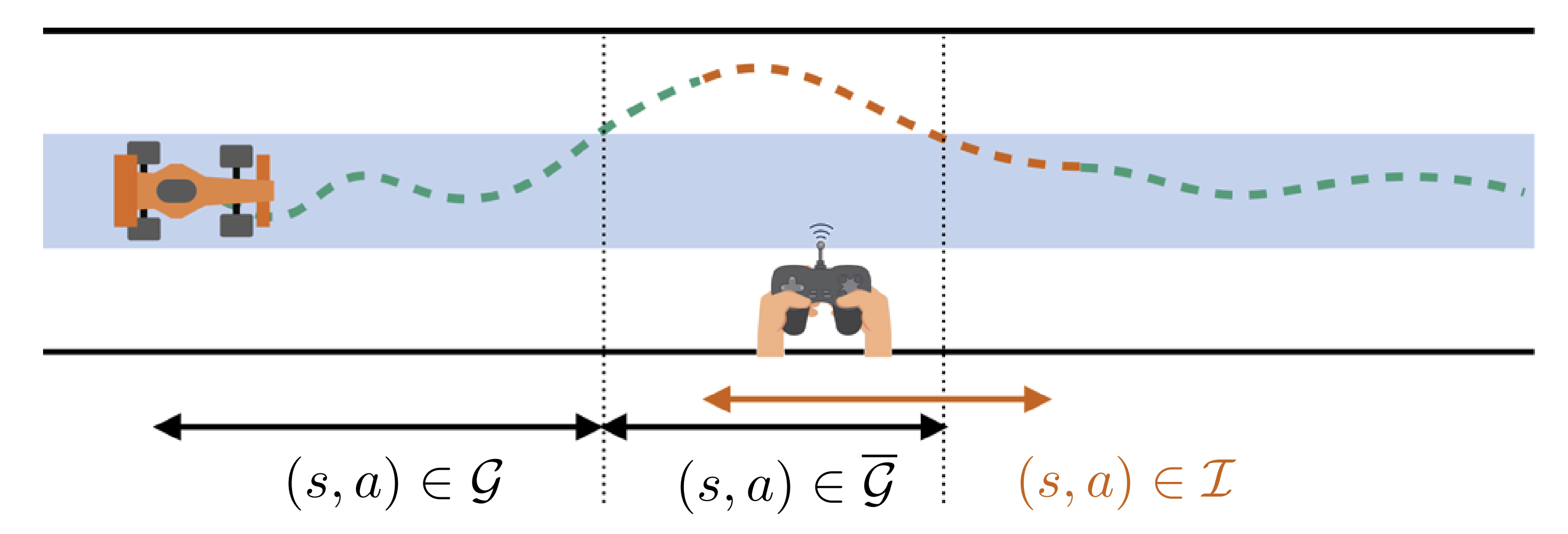

Expert intervention learning is a direct improvement over HG-DAgger that attempts to minimize human interventions by enforcing the learner to stay within a “good enough” region as defined by the human expert. This region is implicitly defined by the human expert by when they choose to intervene and release control back to the learner. We can see an example of this for the self-driving car task shown below in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Example of EIL taking place in the self-driving car task. The light blue region defines the “good enough” region. Whenever the car veers away from this region, the human expert intervenes and controls the car back to the good enough region. [4]

We define good enough state-action pairs as belonging to the set \(\mathcal G\). With this, we define

Three key assumptions for the EIL framework are now stated:

- The expert deems a region of the state-action space to be “good enough”: \((s, a) \in \mathcal G\).

- When a robot is in \(\mathcal G\), the human does not intervene. The robot remains in control even though it may select actions different from what the expert would have chosen. Therefore, \(\mathcal G\) must be defined in a manner so that all state-actions are tolerable even if they may be inefficient.

- As soon as a robot departs \(\mathcal G\), the expert intervenes and controls the system back to \(\mathcal G\).

We now formulate the problem as a rewardless MDP where we strive to obtain a policy \(\pi(s) = \textrm{arg} \min_a Q_\theta (s,a).\) Instead of shaping the \(Q\) function using a reward function, we shape the \(Q\) function through constraints that encourage the model to learn human preference. To do this, we first define a scalar \(B\) which acts as the threshold for “good” and “bad”. The constraints can then be formulated as shown below.

- Learn good enough state-actions \(\\ Q_\theta (s, a) \leq B \ \ \forall \ (s,a ) \in \mathcal G\)

- Learn bad state-actions \(\\ Q_\theta (s, a) > B \ \ \forall \ (s,a ) \in \bar{\mathcal G}\) where \(\bar{\mathcal G}\) is the bad state-action set.

- Learn to mimic the human expert during recovery \(\\ Q_\theta(s,a) < Q_\theta(s, a') \ \ \forall \ (s, a) \in \mathcal I, a' \neq a\) where \(a'\) is the expert action and \(\mathcal I\) is the intervention state-action set.

Figure 5. Example sequence showcasing the different state-action pairs belonging to the good enough, bad, and intervention sets. [4]

These constraints are then reduced to a convex optimization problem through the use of hinge loss where

- \[Q_\theta (s, a) \leq B \rightarrow l^1_B(s, a, \theta) = \max(0, Q_\theta(s,a) - B)\]

- \[Q_\theta (s, a) > B \rightarrow l^2_B(s, a, \theta) = \max(0, B- Q_\theta(s,a))\]

- \[Q_\theta (s, a) < Q_\theta(s, a') \rightarrow l_C(s, a, \theta) = \sum_{a'} \max(0, Q_\theta(s,a) - Q_\theta(s, a'))\]

This results in the overall loss function \(l(\cdot) = (l^1_B(\cdot) + l^2_B(\cdot)) + \lambda l_C(\cdot)\) where \(\lambda\) is a tuning parameter. Here, the \(l_B\) terms are referred to as an implicit feedback where the model implicitly learns the good enough region by when interventions start and end. The \(l_C\) term is referred to as an explicit feedback where the model is learns to best mimic the human expert during recovery states. Note that the key contribution of EIL is the inclusion of the \(l_B\) loss term. Without it, EIL degenerates to HG-DAgger.

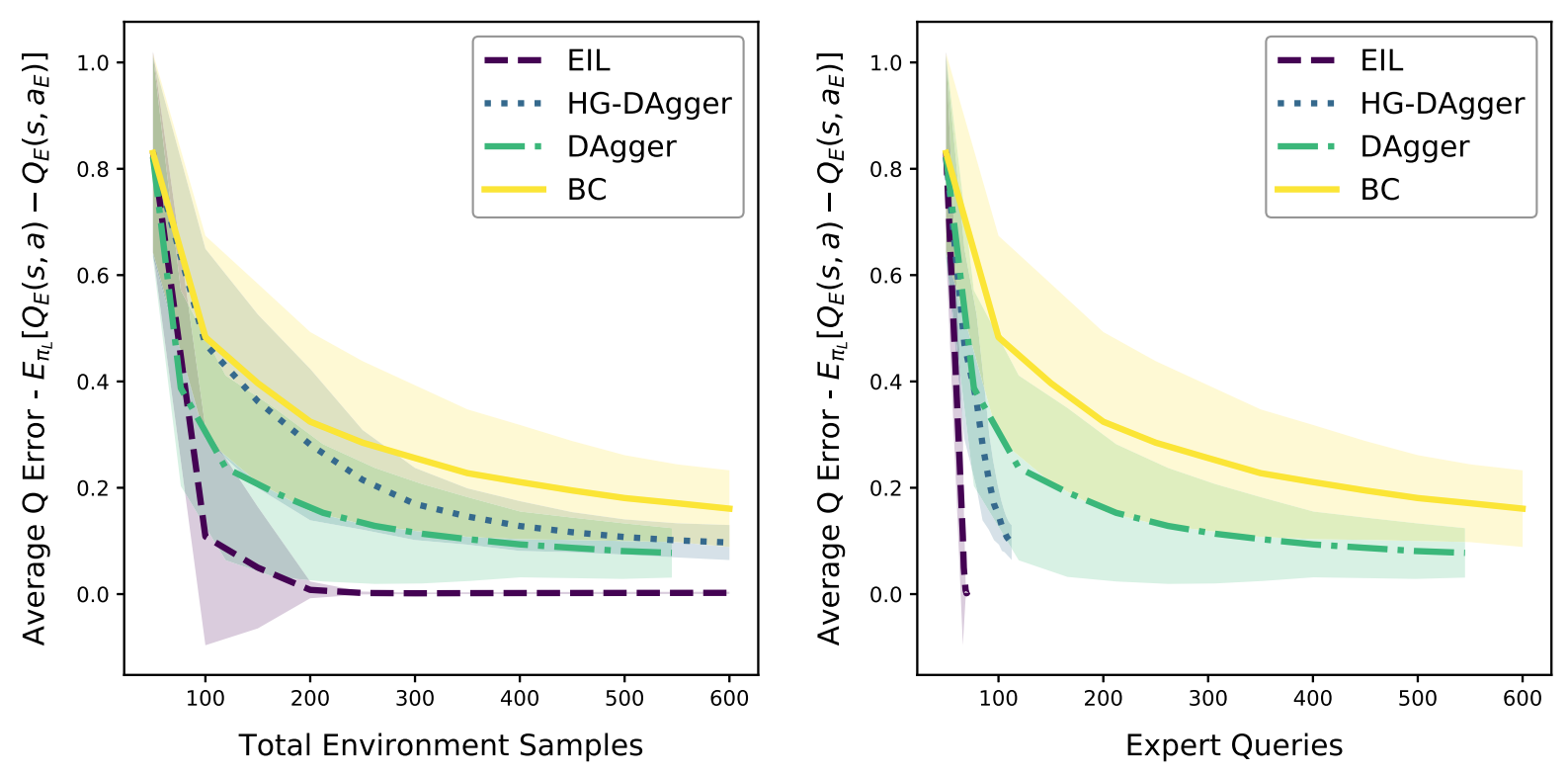

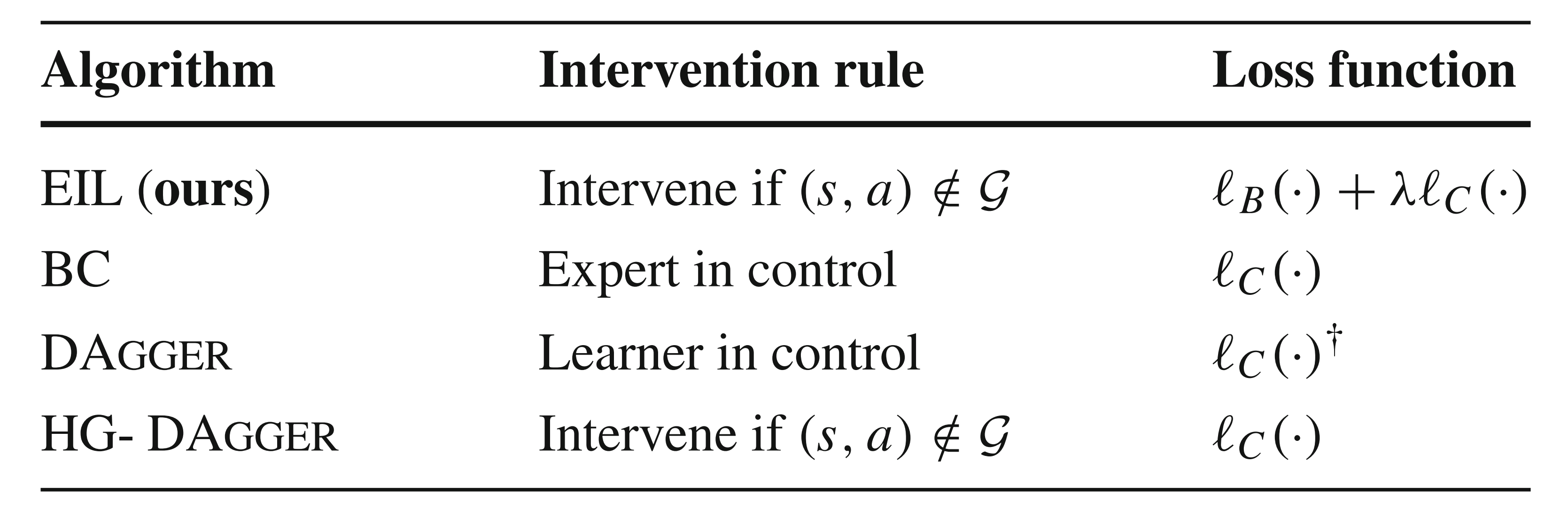

Below, a quick overview of the methods mentioned so far can be seen along with their respective intervention rules and loss functions in Figure 6. In Figure 7, we can see how these listed algorithms perform for a robot self-driving task. Notice that EIL significantly improves over all other methods in reducing the average Q-error with respect to both total environment samples and expert queries (expert state-action labels produced during intervention).

Figure 6. Algorithm comparison. Note that BC stands for behavioral cloning (another word for imitation learning). [4]

Figure 7. Results from a robot self-driving task. Average Q-error with respect to total environment samples and expert queries is plotted for EIL, HG-DAgger, DAgger, and BC. [4]

Human-AI Co-pilot Optimization (HACO)

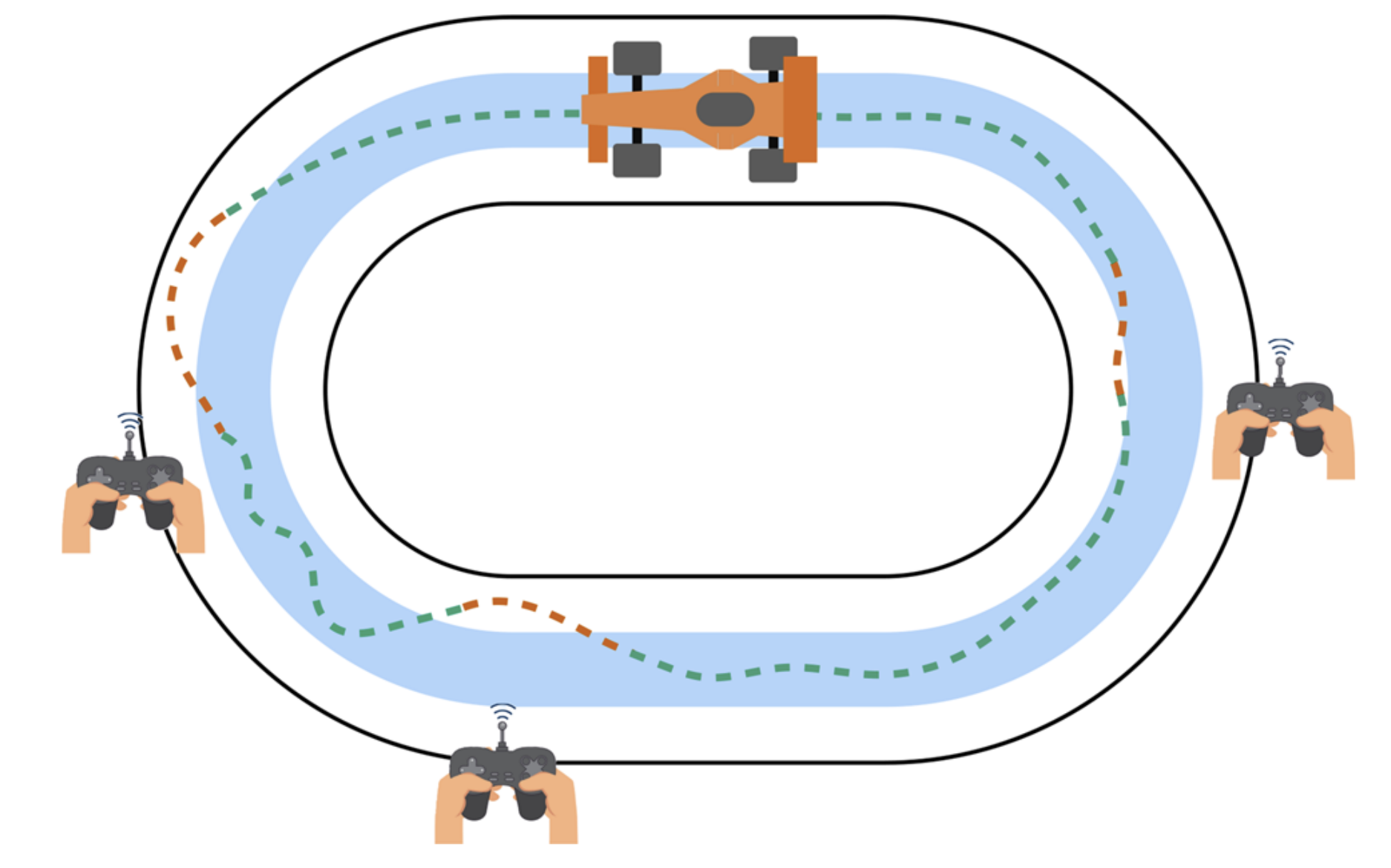

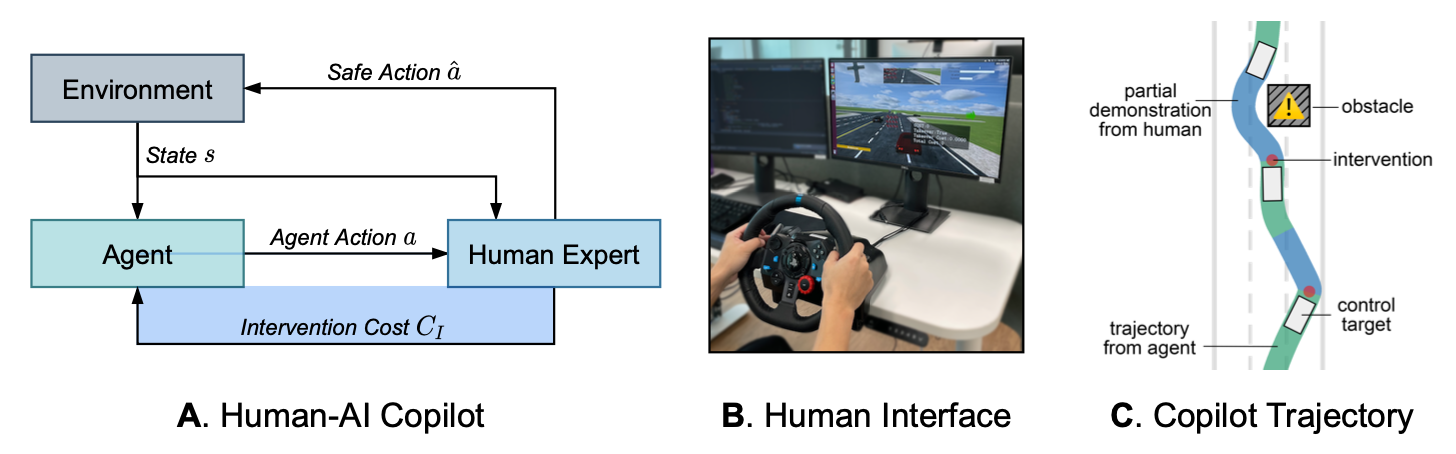

Human-AI Co-pilot Optimization trains an agent from human interventions, partial demonstrations and free exploration. The agent does not have access to (or need) any explicit rewards from the environment. Figure 8 shows a typical setup for HACO learning in a self-driving scenario where the human expert can take control and drive the agent to safety when needed.

Figure 8. Typical Human-AI Co-pilot scenario for self driving. [5]

Figure 8. Typical Human-AI Co-pilot scenario for self driving. [5]

HACO is an online learning technique which operates similar to EIL where the expert intervenes whenever deemed necessary and the policy is learned using an objective loss function designed to learn human preference. However, HACO directly improves over prior methods by introducing the following two key characteristics in the learning objective.

- Exploring the actions in the human-allowed action subspace.

- Explicit cost(implicit negative reward) for human interventions.

The first point helps the agent to consider a wide range of allowed actions at a particular state, thereby opening more possibilities whereas the second point helps in reducing human interventions over time to make the agent self-sufficient. Next, we briefly go over the learning objectives that are considered and how they help achieve the above notions.

Majority of learning data in HACO comes from partial demonstrations when the human expert takes over control to drive the agent to a safe state. We record the state action sequence \(\{(s_t, a_{n,t}, a_{h,t}, I(s_t, a_{n,t}), s_{t+1}),...\}\) in a takeover trajectory and add it to our buffer \(B\). Here \(a_{n,t}\) is the action by the agent, \(a_{h,t}\) is the action taken by the human and \(I(s_t, a_{n,t})\) is a boolean which is true if an expert intervention has taken place.

The learning objective maintains a proxy value function \(Q(s,a)\) which is similar to a Q-value function in a general RL setting. The following loss term helps attain the agent actions closer to that of expert in terms of proxy value, thereby implicitly capturing the expert behaviour.

\[\min_{\phi} \mathbb{E}_{(s, a_n, a_h, I(s,a_n))\sim B} [I(s,a_n)(Q(s,a_n;\phi)-Q(s,a_h;\phi))]\]Next, HACO utilizes an entropy regularization technique to encourage exploration of the agent in the allowed subspace by introducing an additional term in the loss which penalizes actions that achieve higher probability at a given state. This forces the agent to consider alternate actions eventually. The combined loss function to learn the proxy value with entropy regularization now becomes

\[\min_{\phi}\mathbb{E}_{B}[(y-Q(s_t, \hat{a_t};\phi))^2+I(s_t,a_{n,t})(Q(s_t,a_{n,t};\phi)-Q(s_t,a_{h,t};\phi))]\]where

\[y = \gamma \mathbb{E}_{a'\sim\pi_n(.|s_{t+1})}[Q(s_{t+1},a';\phi')-\alpha log \pi_n(a'|s_{t+1})]\]Parameters of the proxy Q-value are iteratively updated (or trained) based on the above loss function.

Finally, it incorporates an intervention cost in the learning to minimize expert interventions over time. Whenever an expert intervenes, a cost based on the cosine similarity of agent action \(a_{n,t}\) and expert action \(a_{h,t}\) is accumulated. The net intervention cost \(Q^{int}(s_t, a_t)\) is calculated using the bellman backup to account for future costs.

\[Q^{int}(s_t, a_t) = C(s_t, a_t)+\gamma \mathbb{E}_{s_{t+1}\sim B, a_{t+1}\sim \pi_n(.|s_{t+1})}[Q^{int}(s_{t+1},a_{t+1})]\] \[C(s,a_n) = 1-\frac{a_n^Ta_h}{||a_n|| ||a_h||}, a_h \sim \pi_h(.|s)\]The following equation represents the final objective for policy learning.

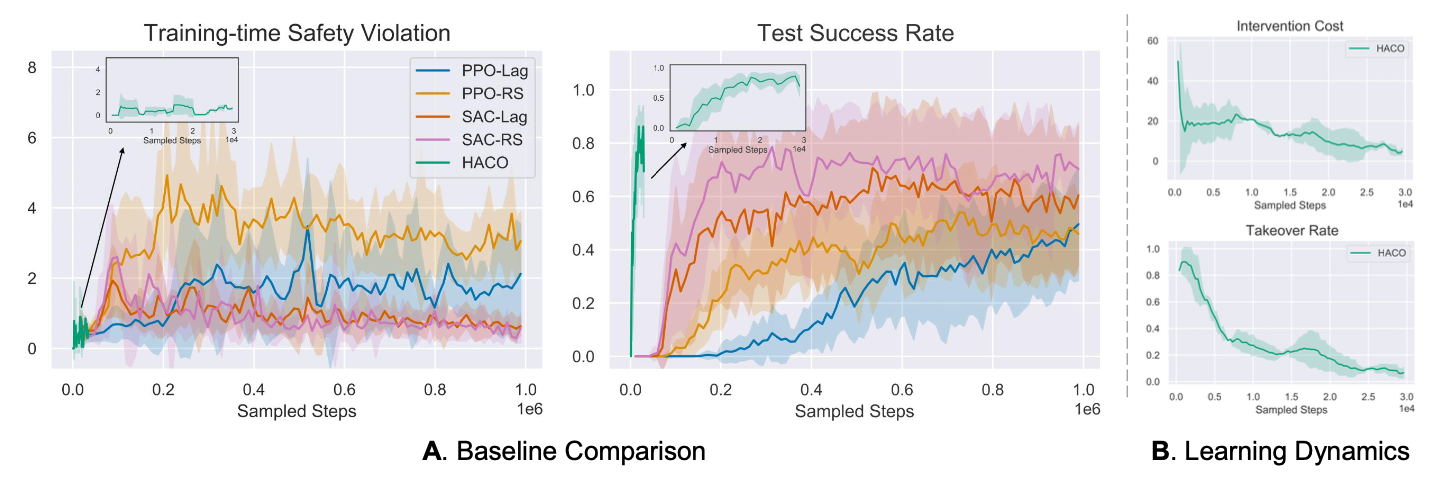

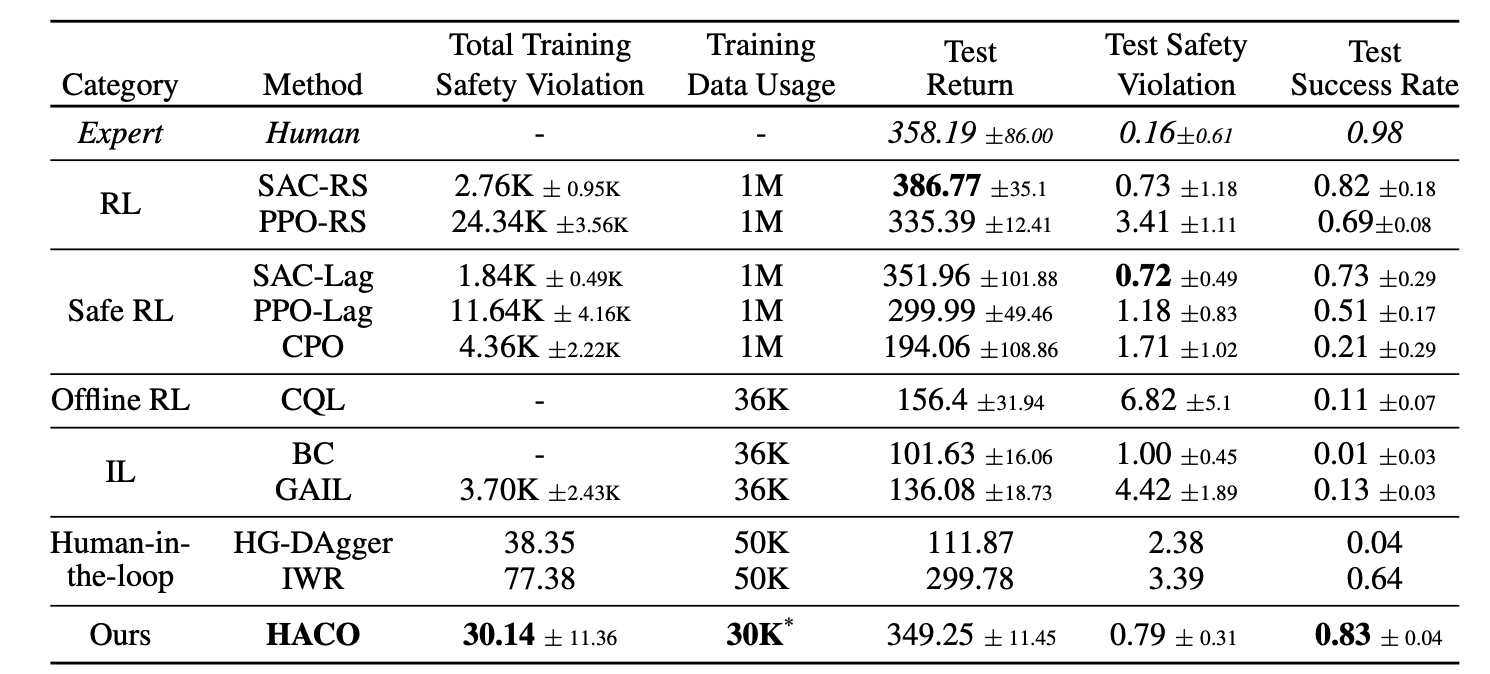

\[\max_{\theta}\mathbb{E}_{s_t\sim B}[Q(s_t, a_n)-\alpha log\pi_n(a_n|s_t;\theta)-Q^{int}(s_t, a_n)], a_n\sim \pi_n(.|s_t;\theta)\]Over the episodes, the algorithm updates \(Q, Q^{int}, \pi\) in an online fashion based on above equations. Therefore, HACO learns from partial demonstrations and human intervention by incorporating three key objectives namely proxy value, free exploration and intervention cost in learning. Figures 9 and 10 depicts results of this method, achieving high sample efficiency and training safety when compared to baselines. In particular, in Figure 10, we can see that HACO outperforms both behavioral cloning and HG-DAgger.

Figure 9. Plots showcasing comparision of HACO results on self-driving task w.r.t baselines. [5]

Figure 9. Plots showcasing comparision of HACO results on self-driving task w.r.t baselines. [5]

Figure 10. Tabled results for comparision of HACO results on self-driving task w.r.t baselines. [5]

Figure 10. Tabled results for comparision of HACO results on self-driving task w.r.t baselines. [5]

Key Differences Summary

| Imitation Learning | DAgger | HG-DAgger | EIL | HACO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method | Train agent using dataset gathered from expert | Trains on aggregated dataset at each step. Gathers new data from expert annotations of sampled trajectories w.r.t current policy. | Expects human intervention. Gathers new data at each intervention step and trains similar to DAgger. | Works on intervention data. Uses optimization objective to bound the agent to good enough states. | Works on intervention data. Optimization considers proxy-value, free exploration and intervention cost. |

| Mode | Offline | Online | Online | Online | Online |

| Improvements | Supervised approach to RL, Handles large/continuous state-action spaces. | Overcomes distribution shift problem by online learning, gathering more expert data | Reduces annotation cost by introducing direct expert intervention. | Reduces expert interventions and encourages learner to stay within a “good enough” state-action space. | Reduces expert intervention + allows free exploration |

| Drawbacks | Distribution shift problem | Require expert to label every learner-visited state which can be unintuitive and difficult. | Does not explictly work to reduce expert interventions over time | Need continuous expert monitoring of the system | Need continuous expert monitoring of the system |

| Annotation Cost | High | High | Low-Medium | Low | Low |

| Sample Efficiency | Low | Low | Medium-High | High | High |

Conclusion

In this paper, we went over key aspects of intervention-based learning including fundamental precursors as well as the current state-of-the-art. We started off with an in-depth overview of both behavioral cloning and DAgger and discussed their limitations. We then discussed one of the pioneering intervention-based learning methods, HG-DAgger, a direct modification of DAgger. Finally, we discussed two state-of-the-art algorithms, EIL and HACO, and explain how these works improve upon HG-DAgger. Both EIL and HACO were shown to outperform behavioral cloning, DAgger, and HG-DAgger in terms of performance and expert label cost.

Despite this, Intervention-based learning is still very much in its infancy, and creating better, more efficient algorithms will be a promising research direction. Particularly, it is left to be seen how intervention-based learning can be used for more complex tasks as much of the current research has used self-driving as the experimental platform. Integrating these algorithms for tasks with much higher degrees of freedom such as robot manipulation will be necessary. Furthermore, there has currently been no experimental comparison between EIL and HACO. Although HACO is an improvement over EIL theoretically, seeing how these two algorithms perform comparatively will be crucial for figuring out the state-of-the-art.

References

[1] Brenna D. Argall, Sonia Chernova, Manuela Veloso, & Brett Browning. “A survey of robot learning from demonstration”. Robotics and Autonomous Systems, 2009.

[2] Stephane Ross, Geoffrey J. Gordon, & J. Andrew Bagnell. A Reduction of Imitation Learning and Structured Prediction to No-Regret Online Learning. AISTATS, 2011.

[3] Kelly, M., Sidrane, C., Driggs-Campbell, K., & Kochenderfer, M. “HG-DAgger: Interactive Imitation Learning with Human Experts”. International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 2019.

[4] Jonathan Spencer, Sanjiban Choudhury, Matthew Barnes, Matthew Schmittle, Mung Chiang, Peter Ramadge, and Sidd Srinivasa. “Expert Intervention Learning: An online framework for robot learning from explicit and implicit human feedback”. Autonomous Robots, 2022.

[5] Quanyi Li, Zhenghao Peng, & Bolei Zhou. “Efficient Learning of Safe Driving Policy via Human-AI Copilot Optimization”. International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), 2022.