Module 7: Human-in-the-loop autonomy - Preference Based Reinforcement Learning

In this survey, we talk about the evolution of human perference based reinforcement learning, with a bunch of examples.

Main Content

Introduction

Reinforcement learning is a branch of maching learning, where an agent in an environment is trying to take actions in order to optimize a reward function. Lots of real-world tasks can be classified as reinforcement learning problems. For example, autonomous vehicles needs to take quick actions in response to the traffic environment to avoid safety issues like collisions; real-time strategy game playing requires the player to make decisions and take action according to observations and changes of the environment.

A classic reinforcement learning setting includes a pre-defined reward function, which gives feedback on the actions of the agent and guide it towards a better performance. The reward function is usualy defined according to the final goal of the agent, which may be indicated by several obvious metrics or less obvious metrics derived from expert knowledge and demonstrations. However, as the task of reinforcement learning becomes more and more diverse and complex, it is not always straightforward to design a reward function, especially with hidden goal metrics or tasks which are hard for humans to demonstrate. However, for many of these tasks, it is fairly easy to let human score, or give preferences to actions of the agent. This is why human preferences get into the process of reinforcement learning tasks.

For the rest of this survey, we will talk about several works where human preferences get involved. We will show how there has been a change from direct human feedback to reward functions derived from human feedback, and how various techniques have been introduced in the training process for a better efficiency as well as performance.

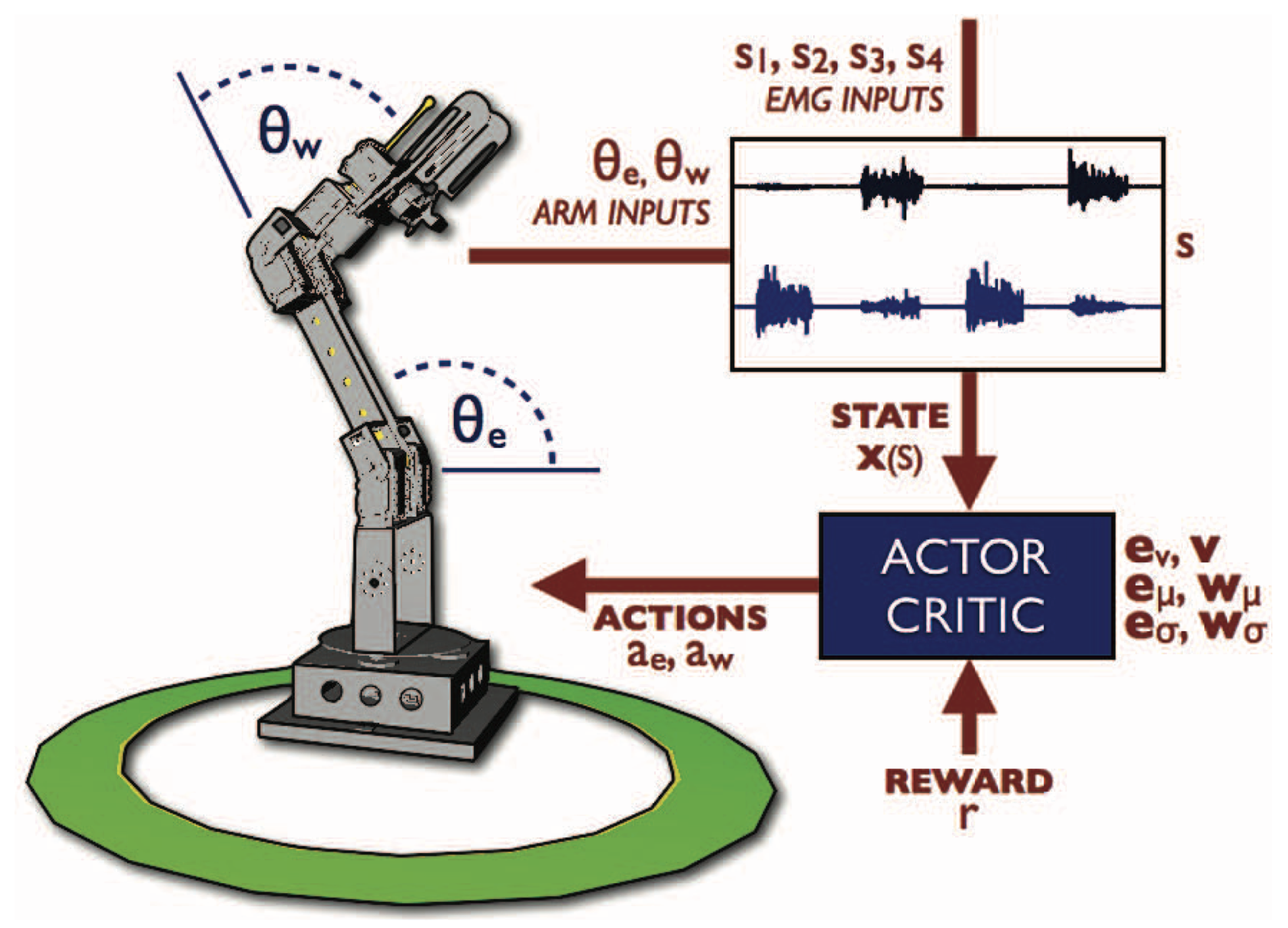

Direct Human Feedback

In the early stage of human preference-based reinforcement learning, human preferences are directly used as the feedback for the agent. For each training iteration, the human gives they preference on the agent’s actions, which is corresponding to a value in the reward function. This method is simple and has been effectively used for many tasks. One example is [1], which aims to let a robotic arm learns a control policy in two ways, either with a pre-defined reward or with live feedback given by a human. The two key parameters of a robotic arm’s gesture are its elbow and wrist joint angles, shown in Figure 1. For the pre-defined reward, the robot only gets a positive reward of 1 when both angles are within 0.1 radians of the target angles, and get a negative reward of -0.5 for all other cases. For the human feedback reward, every time the human is shown a 3D model of the robotic arm’s target gesture, as well as the current gesture. And the human can choose to give either a positive reward 0.5, or negative reward -0.5. Since there is a discrepency between the frequency of training (happens in a millisecond scale) and the frequency of human feedback (A human can only give a feedback every few seconds). For training iterations with no human feedback, the reward value is a decayed value of most recent human reward according to the time elased since last feedback, and reaches 0 when the decayed value is below a threshold.

Figure 1. The two joint angels of a robotic arm

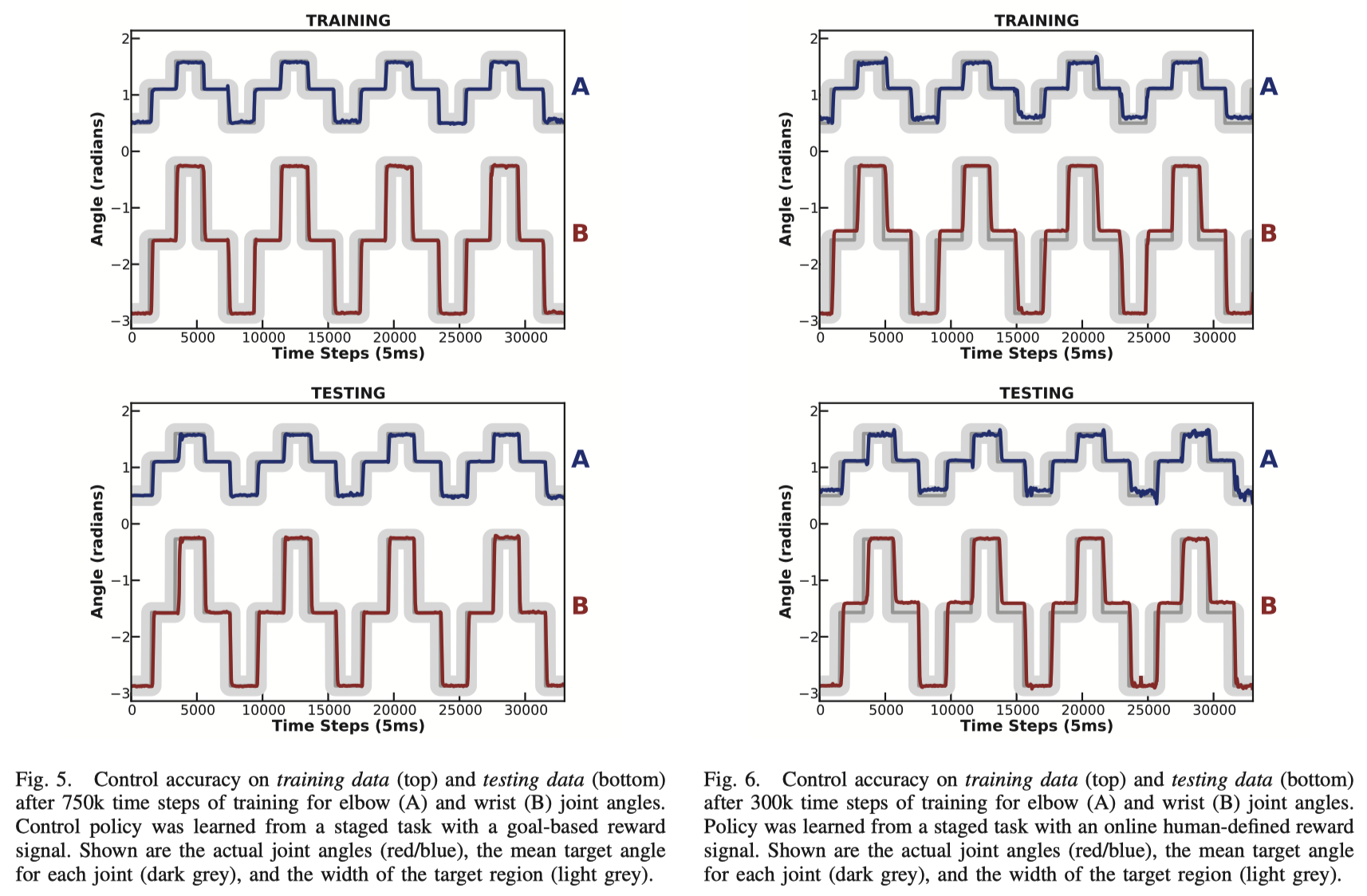

The authors compares the training performance of two methods, depicted in Figure 2. Figures on the left and right are performance of training with a pre-defined reward for 750k time stamps and human feedback for 300k time stamps, respectively. Figures on the top and bottom are performance of training on training data and testing data, respectively. The dark grey line is the target gesture and the light grey line is target region, which denotes a range of desired behavior. We can see that although the performance with human feedback is not as precise as that of pre-defined feedback, it still achieves an acceptable performance. And note that training with human feedback only takes less than half of the time as the other method. Also, each training process only requires less than 10 minutes of user interation. Training with human feedback may seems unnecessary in this case, but it can be much more helpful in occasions that a clear and efficient reward function is not easy to define with obvious metrics.

Figure 2. The training results using two methods.

Reward Function Trained with Human Preferences

Although reward with direct human feedback can be simple and effective, it is not scalable in more complex tasks. Direct human feedback means that human must give feedback for every action the agent takes, and the training process cannot proceed when human feedback is not available. Therefore, a new method has been introduced and advanced, where the reward function is derived from human feedback. A classic reinforcement learning setting with human perferenced-trained reward includes 3 iterative processes: The agent gives a set of actions, or a trajectory based on its current policy; the human gives feedback on the agent’s actions; the human feedback are utilized to generate or update a reward function to guide the agent’s policy.

Human feedback can comes in a lot of forms, including scores, comparison results and ranking of trajectories. Every method using one of the three has been evolving since its introduction. For exmaple, APRIL [2] takes the method with trajectory rankings, and enhance it with active ranking, which is a method to reduce the number of pair-wise comparisons with approximation when giving rankings between new trajectories and current best trajectory. Experiments show that it can effectively reduce the number of comparisons to make the training make progress faster. However, the approximation method also eliminate the approximate optimality guarantee of existing methods, which may show in real-world tasks that the agent’s performance is not as good as current methods with the same number of iterations.

Scaling Up to Deep RL: Async Training, Demonstrations and More

In more recent efforts on preference based reinforcement learning, researcher have been adding a lot of techniques and enhancement, trying to give this method better scalability so it can be used for more complicated tasks, as well as better performance. [3] is a pretty popular work on this topic. We will take about 4 improvements it make to existing works, two for scalability and two for performance.

The first improvement is asynchronous training. Previously, agent trajectory generation, human feedback and reward update happens syncrhonously. This is not scalable, since there is a discrepency between the speed of agent evolution and the speed of human feedback. Naturally the iterations of agent trajectories and reward update can happen much faster than humen feedback (milliseconds vs. seconds). Synchronous training requires the agent and reward to wait for human feedback to produce before it can take the next action. Asynchronous training on the other hand, allows the three components to evolve each in their own pace, dramatically improve training efficiency and scalability. Another scalability improvement introduced in [3] is to provide short clips of trajectories for the human to compare instead of the full trajectories. The authors find that the length of time the human spend to compare each set of trajectories is about linear to the length of trajectories clip, as long as they are long enough beyond a threshold. By providing short yet reasonable-lengthed clips instead of long full trajectories, the human evaluator spend less time on each comparison, further contributing to the training efficiency.

In terms of performance, the work also takes a bunch of measures. It uses a technique called ensembling, which means training multiple reward functions with different human feedback samples and define the normalized average of these rewards as the final reward function. This method is empirically found helpful in terms of performance. Another improvement it makes is assuming that the human has a 10% probability to make mistakes and reflect it in the reward training loss function. This makes the training goal more realistic and accurate.

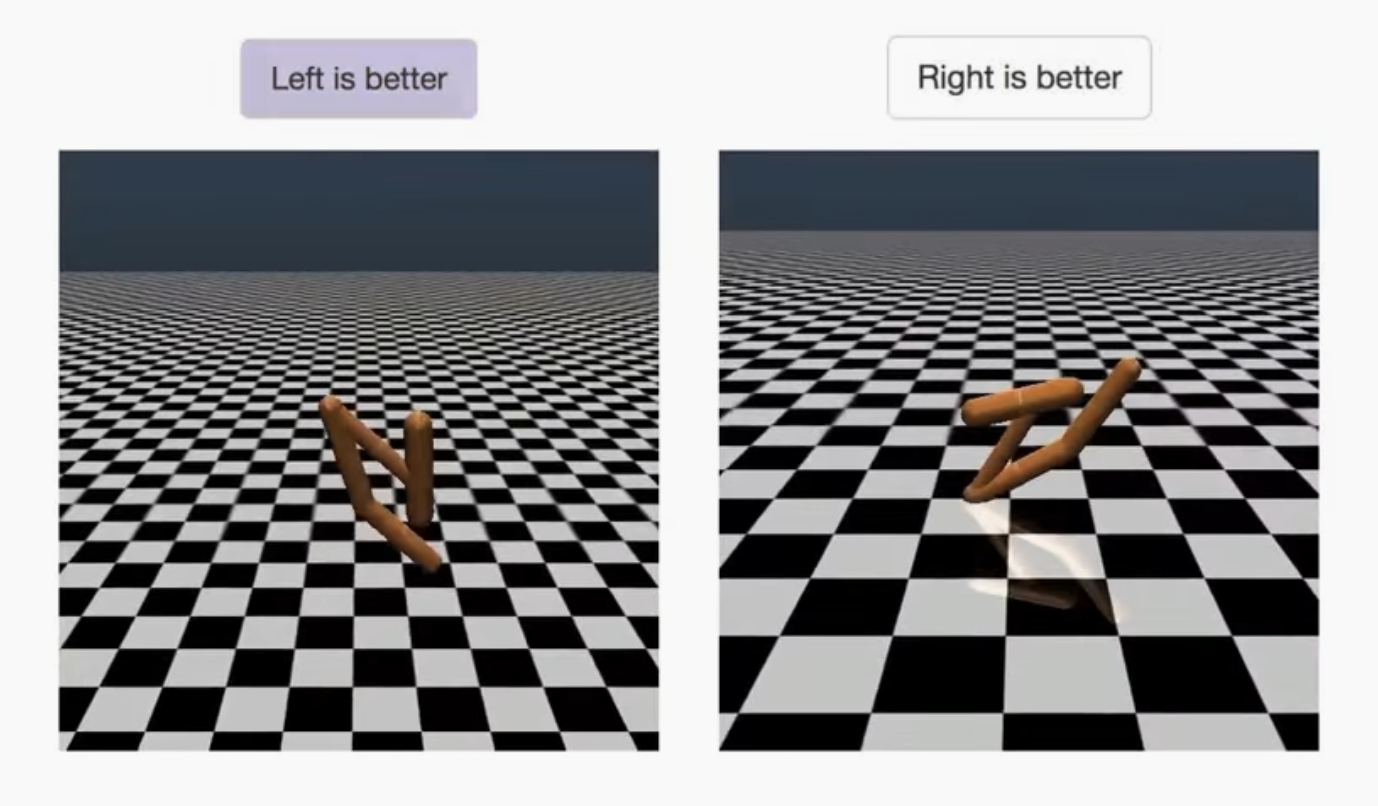

The human feedback of [3] is given in the form of comparison results. The human operate in an interface looks like Figure 3. For each pair of trajectories, the human is shown two trajectory video clips where the agent is trying to perform a task, and they need to choose the better-performed one. A video demo can be found here on YouTube.

Figure 3. The user interface to give feedback.

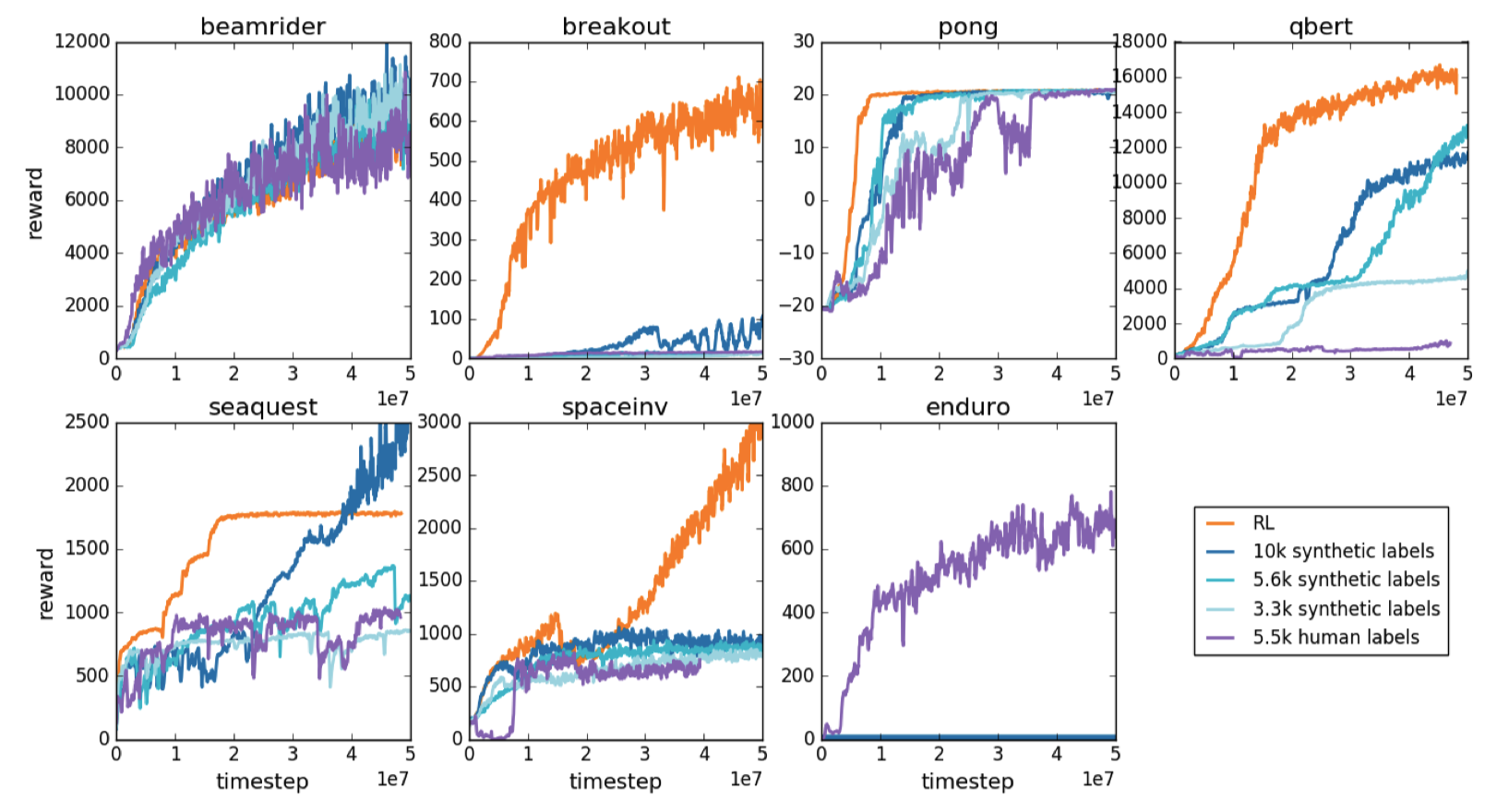

[3] is evaluated on two systems, MuJoCo robotics tasks and Arcade Learning Environment Atari games. Three methods are compared: traditional reinforcement learning with pre-defined reward function, i.e., game scores (RL), reward function trained with comparisons in terms of the real reward function values (synthetic labels), and reward function trained with human feedback (human labels). Here we show its performance on Atari games in Figure 4. We can see that human label method can achieve decent performance, with totally no help of the real reward function. On average, 2 human labels are as effective as 1 synthetic label, as human labels may suffer from problems such as human mistakes and unbalanced label rates from different evaluators.

Figure 4. The performance of [3], compared against three settings.

The authors further enhance their work one year later, by introducing expert demonstrations in the approach [4]. Demonstrations are utilized in two ways: On one hand, the policy is pre-trained before the reinforcement learning process with the demonstration using behavioral cloning, a method to derive policies from demonstrations. On the other hand, these demonstrations are also used to compose comparison results. The expert demonstrations are each randomly paired with the trajectory of the agent, and directly prefered as we assume that the expert is much better than the agent. These comparisons are also fed into the process of reward training. The main limitation of this technique is that not every task can be demonstrated by human. That may be the reason why this work is not evaluated awith robotics tasks, as the robot has different ergonomics as humans, making it impossible for human to demonstrate desired behaviors.

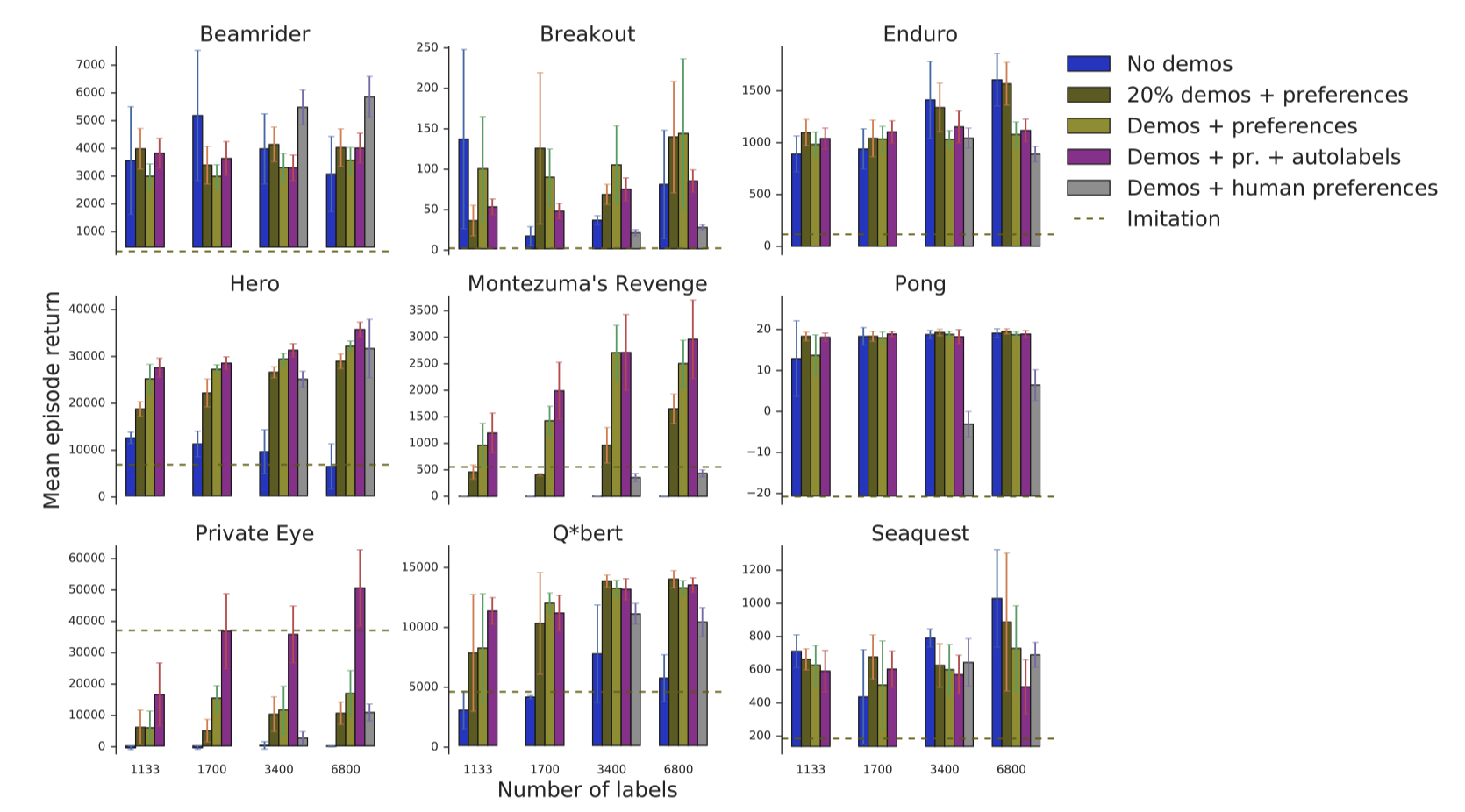

[4] is also evaluated on Atari games, and the authors selected [3] as the baseline. The evaluation results are shown in Figure 5. We mainly compare the performance between [3] (No demos), demonstrations used only in pre-training (Demos + preferences), and demonstrations used in both pre-training and comparison generation (Demos + pr. + autolables). We can see for most of the games, the new method achieve a better performance. One interesting is that for all three methods above, the syntactic labels are used. When using human labels (Demos + human preferences), performance in most games are inferior. This can be taken as another evidence that human labels are still error-prone and less effective.

Figure 5. The performance of [4].

Unsupervised/Semi-supervised Learning and Data Augmentation

The most recent works in this field have been introduced to solve new problems: Although human can give effective preference feedback to RL agent to learn a good policy, such approach is only feasible when the feedback is both pratical for a human to provide and sufficiently high-bandwidth. However at the beginning of RL training, the RL agent’s behavior is very random and doesn’t show meaningful and understandable semantic information to human evaluators and thus the feedback is less useful. Moreover, the expensiveness and slow-speed of human evaluation prevents the agent to get enough amount of feedback information to update its reward and policy. To solve these problems, researchers use unsupervised/semi-supervised learning methods to generate more training data without increasing human preference labeling effort.

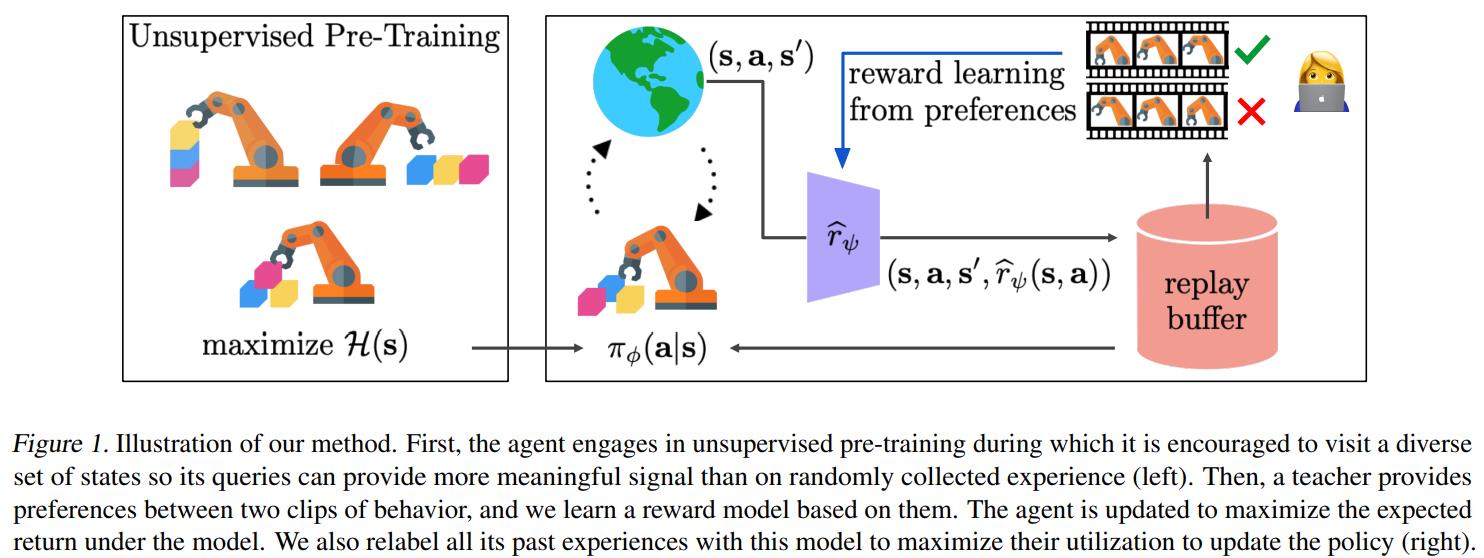

In Pebble [5] algorithm, the RL agent, at its early training stage, doesn’t ask for feedback from humans, instead, it optimzies policy using the intrinsic reward (that is to explore more diverse states and actions and reduce uncertainty). After Collecting enough breadth of state-action sequences, it provides clip pairs to human evaluators, and now human can give more reasonable feedbacks. Pebble then uses human’s preference-based feedback to optimize its reward function, which is a neural network in this case. Contrast to previous method that uses updated reward function to calculate the agent’s current behavior and optimize the policy, Pebble has a replay buffer storing all previous state-action sequences and it uses updated reward function to relabel all these sequences as training data. The relabeling technique greatly increases avaiable training data amount and enables the agent policy to reflect the time-varying reward function more quickly.

Figure 6. Pebble illustration.

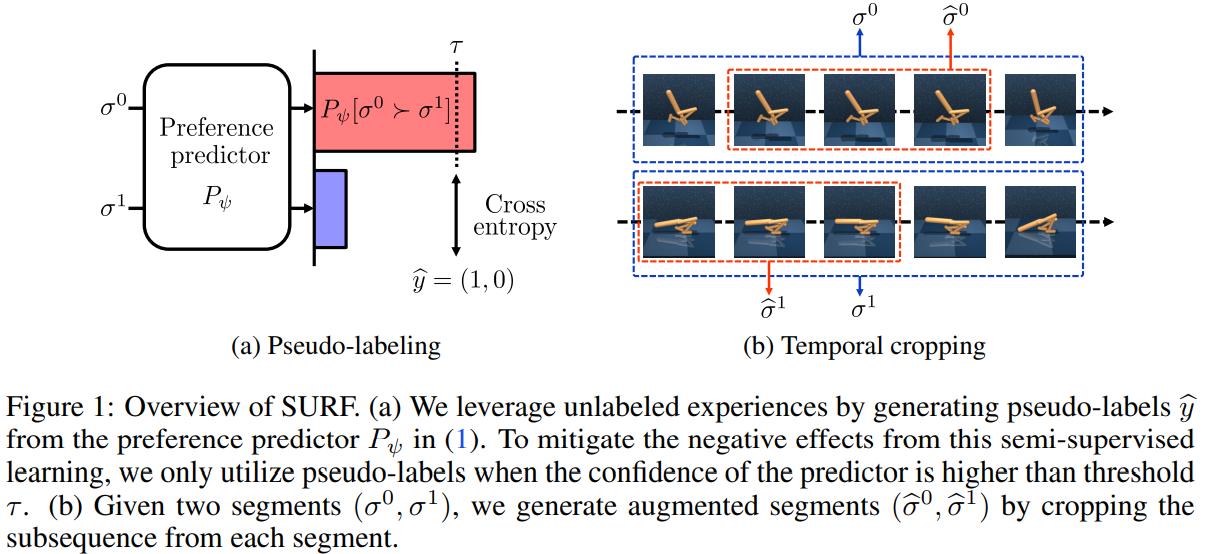

Surf [6] algorithm is orthogonal to Pebble, and it can be directly applied to Pebble to further reduce human effort without performance loss. Surf uses semi-supervised learning to utilize a large amount of unlabeled samples with data augmentation. Same to Pebble, it uses a clip’s accumulated reward calculated with current reward function as the predicted preference towards the clip, and use human evaluator’s preference feedback as real label to compute the prediction loss and optimize the reward function. What Surf further does is to predict preference for more sample clip pairs, and choose these with high confidence (preference of one option is above a threshold and close to 1) as pseudo-labeled data, using them together with labeled data provided by human to compute loss and refine the reward function. Another improvement of Surf is temporal cropping for clip pairs. Temporal cropping means randomly select two continuous sub-clip of the same length respectively from the clip pair, and assign them the same preference of the complete clip pair before the cropping. Cropped clip pairs are also used to compute preference prediction loss and refine the reward function.

Figure 7. Surf overview.

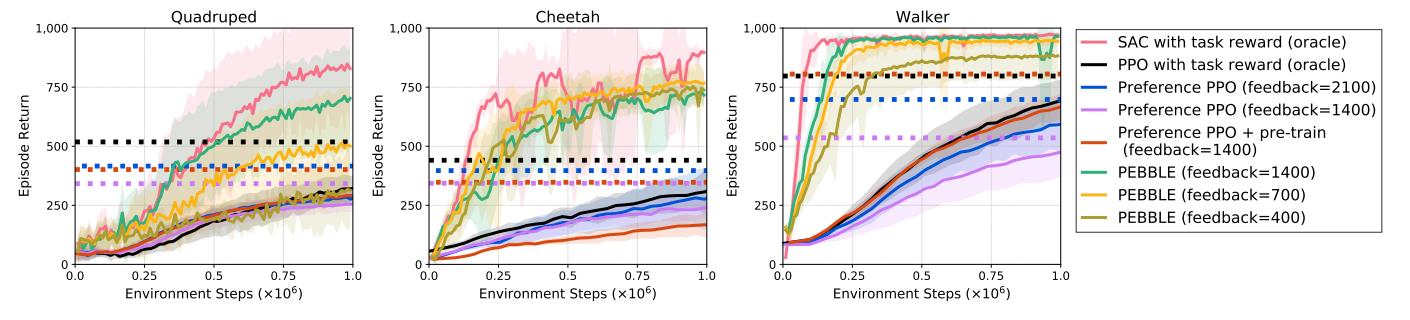

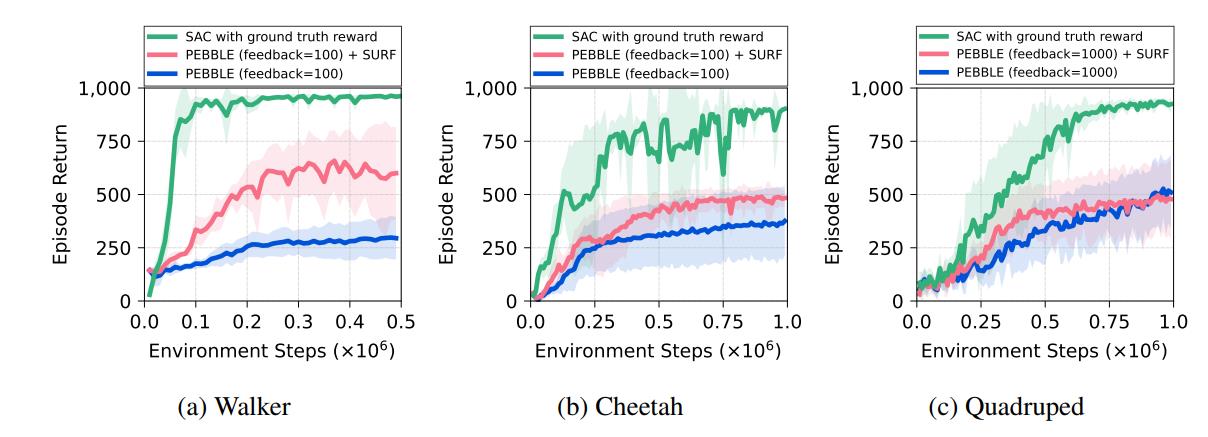

Images below show the evaluation of pebble and surf algorithm on three different locomotion tasks. Pebble, compared to other preference-based algorithms, approaches the reward with gold reward function with the fasted speed and requires much less human feedback. When feedback amount is insufficient, surf when used together with pebble can further improve the return compared to bare pebble using the same amount of feedback.

Figure 8. Surf evaluation.

Figure 9. Surf evaluation.

Discussions and Future Work

Human perference based learning has gone a long way and the works we introduce here uses vastly different application for evaluation, so it may not be that easy to directly compare their performance. But we can clearly see two trends in the evolution in this field: First, researchers are always trying to improve the efficiency of training with human perferences: Direct human feedback is not efficient so we use feedback to train the reward function instead; Synchronous training is not scalable so we train the system asynchronously. Also, tons of techniques, which have been proven helpful in other fields of machine learning, have been introduced in this field as well to improve the performance of ths sysytem. These two trends leads to two promising directions of future work. Researchers will continue trying to make each human feedback more helpful, and they will also further improve the performance of the system with new techniques.

Reference

[1] Pilarski, Patrick M., et al. “Online human training of a myoelectric prosthesis controller via actor-critic reinforcement learning.” 2011 IEEE international conference on rehabilitation robotics. IEEE, 2011.

[2] Akrour, Riad, Marc Schoenauer, and Michèle Sebag. “April: Active preference learning-based reinforcement learning.” Joint European conference on machine learning and knowledge discovery in databases. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2012.

[3] Christiano, Paul F., et al. “Deep reinforcement learning from human preferences.” Advances in neural information processing systems 30 (2017).

[4] Ibarz, Borja, et al. “Reward learning from human preferences and demonstrations in atari.” Advances in neural information processing systems 31 (2018).

[5] Lee, Kimin, Laura Smith, and Pieter Abbeel. “Pebble: Feedback-efficient interactive reinforcement learning via relabeling experience and unsupervised pre-training.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2106.05091 (2021).

[6] Park, Jongjin, et al. “SURF: Semi-supervised Reward Learning with Data Augmentation for Feedback-efficient Preference-based Reinforcement Learning.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.10050 (2022).